Jennifer Reeves' Fear of Blushing

I've been enjoying a brief retrospective of the work of New York-based experimental filmmaker Jennifer Reeves here in San Francisco. She says she wants to be the last person to leave the sinking ship that is 16mm film, and I can see why. Like many avant-garde filmmakers, she wades deep into the material by hand painting frames, placing chemicals onto the film to create colors and shapes, and otherwise manipulating her pictures in ways that aren't possible with video. Film is on its way out, and I'm amazed and excited by what's possible on video these days. See the beautiful films of Pedro Costa or Jia Zhangke or Alexander Sokurov for a few examples. But taking 16mm film from the toolbox of an artist like Reeves — every day, less of the stock is being manufactured, fewer labs are processing it, and fewer venues have equipment for showing the final product — is a little bit like telling a painter that, sorry, we won't be manufacturing canvas and oil paint in the future. Try something else. Start from scratch. With a dramatically different medium.

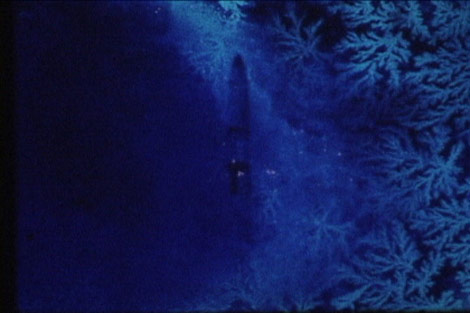

Reeves has begun to work with video, too, and even if it's just a hedge she's achieving some pretty amazing results. She created Light Work I by shooting video footage of her laboratory as she worked on a 16mm film called Light Work Mood Disorder. So Light Work I is like an avant-garde behind-the-scenes documentary, and although it's a video, it captures macro views of defiantly analog processes: swirling paint, cockeyed wall projection, and sewn frames of celluloid. (Michael Sicinski is the guy to read on this sort of thing, although some of what he describes are actually elements of Light Work Mood Disorder, shown second-hand in Light Work I.)

What I liked most about the San Francisco retrospective were the two venues: the first night was at the Artists' Television Access in the Mission and the other two nights were at the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts downtown. The Yerba Buena screening room is a fine place for a screening, but even with your eyes closed you can feel the difference between this hermetically humming museum space and ATA's lofty, wooden storefront, where the projections are visible from the Valencia Street sidewalk. When the film starts at Yerba Buena, you'll hear some pops from the speakers as the soundtrack kicks in; at ATA, you'll hear the galloping clatter of the projectors sitting on a table at the back of the room.

That's projectors, plural. Many of Reeves' abstract works require two projectors that play two reels at once, either superimposing one frame onto another or projecting two side-by-side frames, synced up manually by Reeves so that sometimes you're seeing two independent images and sometimes you're seeing one wide image, "Light" on the left, "Work" on the right. I'm not sure which is more tangible, the cones of light above our heads or the nearly graspable patter of two machines cranking through 24 frames per second, another feature lost in the switch to video, like the incidental noise of a vinyl turntable.

Reeves originally conceived Light Work Mood Disorder for four projectors, hence the four-word title. But even an avowed fan of 16mm film occasionally bows to practicality.