—• CONTENTS •—

— Errata Movie Podcast —

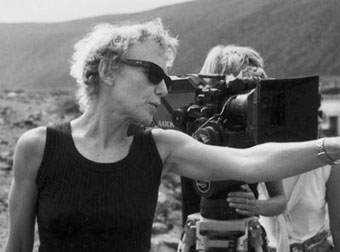

At the Toronto International Film Festival in September I talked with filmmaker Claire Denis about her latest film, the enigmatic L'Intrus. This article appears in a rather different form in the December/January issue of Paste Magazine.

"My films, sadly enough, are sometimes unbalanced," says filmmaker Claire Denis as we sip tea at the Toronto International Film Festival. "They have a limp or one arm shorter or a big nose, but even in the editing room when we try to change that, normally it doesn't work." I'm taken aback, but if I were to do a spit-take right here and now, in front of one of my favorite directors, well I'd turn red as a beet and might never recover. Denis' films are as graceful as they come, bold and musical, somehow warm and intelligent at the same time, and they're so subtle that they often seem to work on a subconscious level. Revisiting one of her movies invariably turns up something new, something placed carefully in the flow of the story by a sure and steady hand, something I can't believe I didn't see the first time. A limp? A big nose? To me they're more like Fred Astaire.

"And I'm not proud of that," she continues. "I would like to be more neutral, so editing would be more like a feast — let's try this, let's try that — but it never works, and it's painful sometimes." She's not being coy. She was just as self-deprecating after a screening of her new film, The Intruder (L'Intrus), the day before we spoke. She took the microphone and stood before a quietly perplexed audience that seemed eager for her to shed some light on the film's mysteries. She offered a few thoughts — "for me it's this idea of intrusion, that there are things in your life that you want and reject... that is very strange, to want something and at the same time you are tired of it" — but when one viewer, unsatisfied with her comments, said he'd stick to his own interpretation, she replied, "It's probably better, anyway. Maybe my interpretation, now that the film is finished, is no longer necessary." What may sound like indifference is anything but; over tea she tells me, "You know, when I am shooting, every moment is strong, every moment is important. I am interested in these moments... but I get a cold wind blowing on my neck and I think — oof — this is going to be hard for Q&A."

The Universe is an Ellipse

Despite Denis' apprehension about editing, watching her movies is something like a feast, and not least because of how her films are edited. Her hallmark is an elliptical storytelling style that requires an active audience. Her movies aren't puzzles, necessarily, but they're full of gaps and undercurrents, and she trusts the audience to assemble the pieces.

In his praise of her first film, 1989's Chocolat, a semi-autobiographical story about a white French family living in colonial Africa, film critic Roger Ebert wrote, "it is made with the complexity and subtlety of a great short story, and it assumes an audience that can understand what a strong flow of sex can exist between two people who barely even touch each other." It's a statement that might surprise some people who've seen the movie, since the film shows no sex and none is talked about. But he's right. The words that aren't said in Chocolat could fill volumes. The movie compares the racial divide in that part of the world to the horizon, a steady line that separates the sky from the earth. You walk toward it, and it moves back. Of all the characters in the movie, the family's African servant Protée has the deepest understanding of the social rules that everyone is living under, but the movie conveys his enormously complex outlook with very little dialog. He's a nearly silent presence in a house full of chatter. As a result, Chocolat is a movie for adults, in the very best sense.

Many of the scenes in Nénette et Boni take us into Boni's fantasies. The payoff comes in the movie's final moments. It's a sudden shock, but whose fantasy is it? Denis wouldn't be so careless as to include a random fantastical act, detached of anyone's brain. This scene is the sort of thing that Boni would dream up, but the glimpses of Nénette sleeping lead me to believe that we're seeing her image of a Boni-style fantasy, one with a boldness that she can't muster on her own, the merged thoughts of siblings. My God, the things Denis can do with film.

Maybe this maturity is to be expected from someone who made her first film at the age of 40, and then only after she'd worked as an assistant director for legendary filmmakers Jacques Rivette, Wim Wenders, and Jim Jarmusch. Denis (pronounced duh-NEE) is the co-writer of all of her films, not just the director of other people's stories, and she draws inspiration from a wide variety of human expression — music and novels, Neil Young and William Faulkner — and from her own experience growing up in Africa and France. But she somehow combines it all into films that are both incredibly cohesive and truly cinematic. Where a novelist might write what a character is thinking, Denis will suggest something similar in a fleeting shot with a subtly-realized but highly accurate point of view.

The Heart-Stopping Intrusion

The Intruder is Denis' tenth feature, and once again she draws on an eclectic range of sources. The original inspiration came from Robert Louis Stevenson's writings about the islands of the South Pacific and the paintings of the post-impressionist artist Paul Gauguin who lived the last years of his life in Tahiti. The movie also recalls F.W. Murnau's last film, Tabu, which takes place on and around Bora Bora.

Denis' film may build on those sunny works, but it begins in the opposite hemisphere, along the snowy, mountainous border between France and Switzerland. It's a landscape that's rife with symbolism, where the people seem determined to keep each other at arm's length. Guards patrol the border, forests surround lone cabins, and people travel with dogs in front of them for protection. And at the center of it all is Louis, a man who lives alone and has little interest in his son and grandchild in Geneva.

Trouble Every Day includes scenes of a maid alone in the locker room of the hotel where she works. The camera watches an intimate moment of changing clothes from behind a stack of towels. You don't need to see Vincent Gallo to know that he's lurking, you only need to know that Denis' camera does not lurk without good reason. To help you along, at the end of the scene, the camera pivots to show a door swing shut at the end of the hallway.

The central idea and the name of the movie come from a book by French philosopher Jean-Luc Nancy. For decades, Nancy has written about communities and how individuals relate to them. We're never truly separate from those around us, he has observed, even though we may sometimes assign the status of outsider or intruder to some individuals. When Nancy had a heart transplant ten years ago, like a true philosopher he saw it as a metaphor; the same theme that he'd been exploring for years now had a physical, and very close, manifestation. The operation saved his life, but his body began to reject the new heart. It was a foreigner beating in his chest, a life-giving curse. And, of course, for him to receive a heart, someone else had to die. Nancy wrote about the experience and his ambivalence in a 40-page booklet called L'Intrus.

Denis herself has explored similar themes in her films: the colonists in Chocolat, a new soldier who is rejected by a seasoned drill sergeant in Beau Travail, and a woman who allows a stranger to climb into her car, and bed, in Friday Night — intruders and foreigners walking the thin line between acceptance and rejection. I ask Denis if any of her films before The Intruder were inspired by Nancy.

"No, I was not aware of anything. In a way I was even afraid to be too inspired by his text," Denis says. "He contacted me when he saw Beau Travail, because he wrote an article about it. Of course, I had read L'Intrus at that time, and I did a small documentary with him." But it was more recently that Denis made the conscious decision to incorporate Nancy's heart transplant into her latest project. "One day I told him L'Intrus was going to intrude my script."

"But there is a coincidence," she adds. "I was preparing the film and he wrote a small book called Noli Me Tangere about the resurrection of Christ, the idea of resurrection.... I read it while I was shooting and I thought, 'How strange,' because, me, I was inspired by this intrusion of the new heart, this very precise and physical book he wrote about rejection. And now he writes this thing about resurrection, which is another aspect of the film, without me knowing, you know? I had not read the book, and I thought— It's as if we had been traveling in the same train or boat without knowing."

continued:

Resurrecting lost film

Posted by davis

| Link

| Comments

(11)